Sir John Kirk, the British Consul to the Sultan of Zanzibar, received in 1884 a report from his Vice-Consul John G. (Jack) Haggard. The brother of Victorian writer H. Rider Haggard had summarised his adventurous journey from his station on the Island of Lamu to the rebellious Simba, Sultan of Witu. As the Vice-Consul’s more famous brother never visited East Africa, it might be speculated that reports such as this acted as inspiration for his long list of publications from 1885 onwards.

Vice-Consul Haggard to Sir J. Kirk

Lamu, East Coast of Africa, August 25, 1884.

Sir,

I have the honour to inform you that I left this place in my boat at daylight on Monday, the 12thAugust for Kolumbi, with the intention of visiting the rebel Chief, Ahmet-bin-Sultan Komloot, commonly known as “Simba” (the Lion), who now resides in the fortified village of Witu, about four days’ easy journey to the southward of Lamu.

Simba, who is now a very old man and a cripple, is of the Wagunia race of Nelhani-Arab descent, and was formerly King of the island of Patta, about 15 miles to the northward of Lamu. After many years’ fighting and heavy slaughter he was driven from there, about fifteen years ago, by the then Sultan of Zanzibar, who took his island, and Simba fled to Kau on the river Ozy, where he settled, and began to collect round him a new tribe in the place of the one which he had annihilated. After living for a few years at Kau he was again driven abroad by the same power, and this time he migrated to the wilderness and settled at a place called Witu, where he has practically been since undisturbed, and his following, which is composed chiefly of all the malcontents, bankrupts, and felons of the surrounding country, and very largely also of runaway slaves, has, in consequence, become numerous, powerful, and dreaded. These people are now best known by the name of “Watoro,” or runaways, but they call themselves “Watawitu,” with the exception of the inhabitants of a few of the more northern villages, who call themselves “Wakengi,” or the “Restless people,” which is a very good name for them.

Of late years all these people have lived chiefly by plundering the neighbouring Swahili villages, and by selling the captured inhabitants as slaves to the Somalis in exchange for cattle, or not unfrequently back to the Swahilis themselves, from whom they again invariably take the earliest opportunity of restealing them.

Of course, these raids have been productive of much bloodshed and distress, and as the Watoro have grown more and more powerful, so their depredations and enormities have become more and more frequent, and the sense of insecurity experienced by the neighbouring Swahilis shows itself in the fact that less and less land is cultivated every year, for no man now dare work alone in his own field if only a few hundred yards away from his village. The hands of the Watoro are now against almost every man, and almost every man’s hand is against them. Although they live not far from the sea they have but one port open to them, and that is the village of Kipini at the mouth of the River Ozy, the Governor of which place is afraid to deny them entrance.

Some of my objects in visiting Simba were to point out to him the advantages of legitimate trade, and of checking his people’s marauding tastes, and to ask permission for a trader to settle in Witu: having found a Hindi merchant with sufficient courage to attempt it, this man I took with me.

Some four months ago I had written to Simba to propose this visit, but circumstances had prevented me from making the journey until now.

I arrived at Kolumbi at 8 p.m. of the 12th August, after a difficult passage, and finding the small-pox was raging with great virulence there made my whole party sleep in the boat.

To show the disturbed state of the country, on this very day a man and a boy left Kolumbi to go to Harura, a Swahili village contiguous to the Watoro districts; near Harura they approached a fire they saw burning to warm themselves, but round which, unfortunately for the Swahilis, six Wakengi were stretched: they jumped up to seize the Swahilis, and one man captured the boy, holding him by the left wrist, whilst he watched the remainder pursuing the man unsuccessfully. The lad suddenly drew his captor’s knife and stabbed the man twice in the stomach, killing him: the remainder of the party coming up at that moment the boy was stabbed in the back, but somehow he managed to et away then, to die in Kolumbi a few hours later.

On the following morning, the 13th August, I started for Mpecatoni, as early as possible to visit the Headman of Kolumbi in his village, and there saw many poor wretches crawling about in all stages of the disease; the Headman himself had just lost one son from small-pox, he had another one sick, and was himself only then recovering from the illness.

I may remark here that this dreadful malady is creating great havoc in Lamu and all the surrounding districts; in places there is not a house where there is not one dead, and at the little town of Siyu, on the Island of Patta, it is reported that no less than 1,400 people have died during the epidemic.

I arrived at Mpecatoni in four hours and a-half, and that afternoon was seized with fever. On the following morning at daylight, although weak and trembling, I was compelled to start for Kipini, where I arrived in seven hours, feeling comparatively well, having walked through the fever. On the march we met a party of Somalis who attempted to stop my porters, but upon seeing an armed party following they desisted. The distance between Mpecatoni and Kipini is from 20 to 25 miles.

That evening I succeeded in dispatching a messenger to Simba to tell him I had come to see him, and to ask for porters, as I could obtain none, every one being afraid to go to Witu.

Kipini is a small village on the northern side of the mouth of the River Ozy. It is stockaded to protect it from the Watoro, but the defences are in wretched order. The River Ozy at its mouth is about a mile wide, and very shallow at low water, a man being able to walk across. Outside there is a reef right across the entrance of the river, which in the south-west monsoon forms a very bad bar. They say there is a passage in the reef through which small dhows pass in the north-east monsoon, but I could not distinguish it by the eye, even when the sea was comparatively calm.

The plantations round Kipini seemed to be cultivated with more care and better result than those nearer Lamu; this I attribute to the freedom from molestation by the Watoro, it being obviously to the advantage of those people to keep on good terms with the inhabitants of their only port, Kipini. In the centre of every field is a high platform, upon which stands a slave with a pile of stones at his feet and a sling in his hand, the missiles from which must do much more harm to the grain than the birds the man is there to frighten away.

On the 15th August I visited a large ruined town about a mile and a-half to the northwards of Kipini. It must once have been a place of considerable importance, well built of stone, and covering a large area. It is said it was deserted sixty years ago in consequence of repeated attacks from the Galla tribes, who then inhabited the immediate neighbourhood, but I should think the more probable reason was the sudden silting up of the good harbour upon whose shores it was built: what, not so long ago, was a deep and well-protected haven, is now, at low water, an extensive dry sand-bank.

In this ruined town is the interesting tomb of Fumo Liongo, a great Swahili hero and poet, of whom there are most romantic stories extant, and whose exploits are still sung in his own verses, the language of which is written and recited in the ancient classical Swahili tongue, nowadays understood by very few people, if any. There is a story told of Fumo Liongo, something similar to the legend of Achilles and his heel. Fumo Liongo, from his wonderful escapes in battle, was also said to be invulnerable but in one place, and that was his navel. He was supposed to be invulnerable there also, unless stabbed by a blood relation with a copper needle. Some conspirators prevailed upon Fumo Liongo’s son, Sali, to try the experiment, promising him the Chieftainship as his reward if successful. Sali thereupon stabbed his father whilst asleep, but he was immediately himself killed by the conspirators for his cruelty. Fumo Liongo’s grave is still visited by pilgrims.

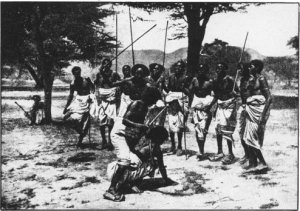

On the afternoon of Friday, 16th August, a party of twenty-nine men arrived from Witu in answer to my letter to Simbha, viz., twenty porters and nine armed men. These people amused themselves in the evening dancing and singing. Their war dances were very savage, but their singing was most melodious and pleasing, and the time they kept wonderfully correct, the whole performance being entirely different from anything I have seen amongst the neighbouring people, and far superior.

I left Kipini at daylight on 17th August for Witu, and passed through a more or less open country, with numerous valleys of fresh water, some of which become dry in the dry season and some do not. On the march we disturbed a large lion right in our path; the spoor of these animals was to be seen everywhere. Witu has been visited once or twice by white men, but not for several years. The soil around is rich and productive, and underneath at various depths is ancient coral rock. Witu lies in low ground, and adjacent to the town is a large valley of very salt water, which curiously enough is full of fresh water fish and none other. I should imagine that all the country in the immediate vicinity of Witu was very unhealthy.

The town itself is in the centre of the densest bush I have seen, about three or four miles round; so dense and so impervious is it, that it gives you the impression of having been artificially planted for defence, and I consider there is little doubt but what it has been so planted. It is strongly stockaded with trunks of trees, but the bush has grown over all the stockade so as to quite conceal it, except at the gates, which are very massive, and can only open wide enough for one man to pass at a time. These gates are always kept strongly secured. When I arrived at 11 a.m. I still found them shut, and it took over a quarter-of-an-hour to remove the obstructions. On entering the town I walked at once to Simba’s stone house, and found him ready at the door to receive me, splendidly dressed; with him were his two sons, Fum Bakari and Mku, and his brother-in-law, a light-coloured Swahili or Arab, called Monyi-bi-Abdallah. After a few minutes’ conversation I withdrew to the house prepared for me. At 2·35 p.m. I returned to Simba, and, reading from notes of the object of my visit, had a long interview. I told him –

1. That I was an officer sent to Lamu and its neighbouring districts by Her majesty the Queen of England to protect British subjects and to encourage trade, with the hopes that the stimulation of the legitimate trade would in time, by making the people more wealthy, tend to check petty wars and disturbances and to encourage agriculture.

2. That I had come to Witu, in obedience to orders, to ask him, in the name of Her Majesty the Queen, to protect British subjects, traders, and travellers, and to help them in their legitimate enterprise by his power and influence.

3. If at any time he had cause for complaint against any British subjects, I asked him to send them or their names to me at Lamu, but not to take the law into his own hands, or to allow his people to do so either.

4. On the other hand, I asked him, if British subjects were injured by his people, that he would see them righted.

5. I asked him not to permit British subjects, in aby way, direct or indirect, to embark in the Slave Trade, and begged that he would inform me of any such attempt.

6. I spoke about trade generally, specifying different articles, and recommended peace and agriculture as the greatest sources of wealth.

Simba promised to attend to all I had asked him, and also remarked he wished me to beg you (Sir John Kirk) to tell the Sultan of Zanzibar that he (Simba) was an old man now, and wished to live and die at peace with all men; and he asked me to do if he could guarantee that his people should commit no further enormities or depredations; this he said he would do.

I then withdrew.

From what passed at this interview I was inclined to think that Simba was sincere in his desire for peace and quiet; but from events which subsequently occurred I imagine he is more or less playing a double game. The common gossip is that Simba is sincere for peace, but that it is his son, Fum Bakari, who is the firebrand. I am inclined to think that, although undoubtedly Fum Bakari is a great rascal, he is more or less made a scapegoat to conceal his father’s and Monyi-bin-Abdallah’s designs.

That evening after dark Simba’s brother-in-law and chief adviser, Monyi-bin-Abdallah, called on me, and asked for a private interview, which I granted.

To my amazement he commenced what he had to say by threatening me.

The burthen of his communications were words or innuendos to this effect:-

1. That I had written four months previously to propose a visit to Simba, and had not come until now; consequently I had insulted Simba, and my conduct merited punishment.

2. That the English had assisted His Highness the Sultan of Zanzibar in taking prisoner some Chief or other at a place called Makelli, through whom until then Simba had been in the habit of obtaining his guns and ammunition, and now that I was in their power retaliation upon me was perfectly just; but, however, there was a loophole by which I might escape, if I myself would consent to run guns and powder for them from Lamu, but if I declined the consequences might be unpleasant. In reply, I expressed with some warmth my indignation at my non-arrival in Witu before now being made a grievance. As for the Chief at Makelli, I declared I had never even heard of the man, and did not know what he alluded; and in reply to his suggestion, that I should run guns, I point-blank refused to do anything of the kind. At that moment happily we were interrupted, and Monyi-bin-Abdallah flew out of my hut in a passion. The man’s manner towards me was so threatening, sinister, and ferocious, that I could not but feel uneasy at my helpless position, in a town full of savages so securely walled that a cat could not escape from it; and I plainly saw from the drift of his remarks that the rumour is not unfounded, that Simba is about to join Mbaruk (the rebel Chief against the Sultan residing near Mombasa), and that the idea had suggested itself to Simba to make a prisoner of me to play me off against any attacks made upon them by His Highness the Sultan of Zanzibar.

I may remark here that Simba can bring about 3,000 men into the field, but not all armed with guns. That night and the following day I had a rather serious return of fever, and in my stifling mud-room, with no ventilation or light, and swarming with rats and every description of vermin that feeds on man, my sufferings were considerable. On the morning of Sunday, the 18th August, I was visited by Monyi-bin-Abdallah, and I positively declining to renew the conversation of the previous evening, he suddenly informed me I could have porters to leave Witu when I chose, so I at once settled to leave on the following morning at daylight.

At 4 p.m. I went to take leave of Simba, whose manner was cold, and I then received his permission for a Hindi trader to settle in Witu. Simba also informed me he should send for my interpreter in the evening to make a communication. My interpreter accordingly went after dark, and Simba then repeated to him, without the threats, all that Monyi-bin-Abdallah had said to me the previous night.

Simba also told my interpreter to ask me, in the event of my still refusing to smuggle guns for him, to beg you (Sir John Kirk) to undertake the business. I have not the least doubt that Simba had ordered Monyi-bin-Abdallah to try and frighten me into compliance, but that failing, for some reason or other he determined to let the matter drop, and appeared in a hurry to get rid of me.

I may remark here that punishment from His Highness the Sultan of Zanzibar sooner or later, seems to be very generally anticipated at Witu, and I consider it would be wise not to dissapoint them, but to destroy the whole colony as soon as possible, and capture their leaders, or, with their rapidly increasing strength, they may very possibly attack him somewhere. Anyhow, if unmolested much longer, the Watoro will succeed in completing the ruin and destruction of this fine country.

Slaves are numerous at Witu, Simba alone possessing 600. The plantations are extensive and fruitful, the soil being very productive; a peculiarly large species of coconut is grown in them, of a superior kind to any I have seen in Zanzibar, Lamu or elsewhere. In addition to Witu there are six principal villages in the vicinity under Simba, the inhabitants of which call themselves “Watoro Witu,” namely, Hassad, Mohonde, Mawasi, Chaoja, Gowgowi, and Mominfoi,; the inhabitants of these seven villages together number nearly 5,000 souls. A little to the northward are several more villages, whose inhabitants call themselves “Wakengi.” The most important of these are Balana, Katana, Balo, and Mtangamakondo. These Wakengi are partially independent of Simba, but he commands them in most things, and only the other day put some of their Headmen in prison for disobeying his orders.

I left Witu on the morning of the 20th before daylight, and arrived at Kipini in five hours.

On the 21st August, after endless trouble in obtaining porters, I started my return journey to Lamu, arriving at Kolumbi on the 22nd. Having loaded my boat I dropped down the creek in the evening, intending to anchor somewhere near its entrance, but a fine breeze springing up I pushed straight on through the night to Lamu, arriving there safely without incident.

I have, &c.

(Signed) John G. Haggard.

Source: Haggard to Kirk, 25th August 1884, FO 403/93, TNA